AIDS and Abolition: Activism Against the Epidemic in Prisons

This article is authored by Emily K. Hobson, from the 2019-20 cohort of the LGBTQ Research Fellowship program at the One Institute.

I am researching the history of activism to confront HIV/AIDS in prisons and jails in the 1980s and 1990s United States. While not widely known or recounted in narratives of AIDS history, AIDS prison activism was widespread, especially in California, the Northeast, and federal prisons. As early as 1986, incarcerated people organized peer education projects to share information on prevention and to advocate for their own and others’ medical care. From outside prisons, activists provided incarcerated people with health information, carried out legal advocacy, and protested for policy change. Moreover, across disparate locations, many activists began to see AIDS and mass incarceration as interconnected. Three complex, interwoven problems—the dismantling of the social welfare state, justified in part by prison spending; the heightened criminalization of drugs and sex work; and the impacts of mass incarceration on community health—helped to fuel the epidemic and to locate it disproportionately in poor, urban, and Black communities. At the same time, homophobic stigma defined AIDS as a gay—and implicitly a white and affluent—disease. Activists who confronted AIDS in prisons brought a seemingly marginal issue into the center of the AIDS narrative, and shone a light on ties between criminalization, austerity, and health, as well as between sexuality, race, class, and gender.

One of the sites where AIDS prison activism held greatest strength was Los Angeles, and one of the most important groups in such activism was ACT UP/LA. Prior to my time at the ONE Archives, I had concentrated my research on AIDS peer education programs run by prisoners. My research at the ONE Archives was the first time I attended to prison activism by ACT UP. As I found sources I faced the need to contextualize prison issues in the group’s broader work, and to understand why the members of ACT UP/LA—predominately white, middle-class, and non-incarcerated—came to care about AIDS behind bars. I became fascinated to see that prison issues won sustained attention in ACT UP/LA, indeed, that concern over prison became a connective thread across multiple dimensions of the group’s rhetoric and work.

Two persistent themes shone through in my research. One was that women stood at the center of ACT UP/LA’s prison organizing. As Benita Roth has suggested, prison issues became a means by which the Women’s Caucus in ACT UP/LA established leadership and framed AIDS as a “women’s issue.” This pattern was not unique to Los Angeles. In the 1980s and 1990s as well as now, women’s prisons saw higher rates of HIV/AIDS, even as men’s prisons saw higher total numbers of people living with AIDS and HIV. Peer education programs in women’s prisons, especially New York’s Bedford Hills, won sustained press attention. Additionally, in both ACT UP/LA and ACT UP/New York, formerly incarcerated women found leadership roles. Mary Lucey, an HIV positive lesbian who had been incarcerated at the Frontera women’s prison, became a prominent leader in ACT UP/LA’s Women’s Caucus, and deepened others’ understanding of conditions faced by incarcerated people with AIDS and HIV. In November 1990, the Women’s Caucus organized an unprecedented protest at Frontera. Over a hundred ACT UP/LA members traveled to protest, focusing their outrage on a segregated AIDS ward known as Walker A. They demanded the provision of medications, adequate nutrition, qualified medical staff, and timely care. A year and a half later, ACT UP/LA led a statewide protest at the California Department of Corrections, occupying the office of the department’s director. As at Frontera, both women and men took part, but women served as prominent spokespeople, and the action framed AIDS prison conditions through an intersectional feminist and queer politics.

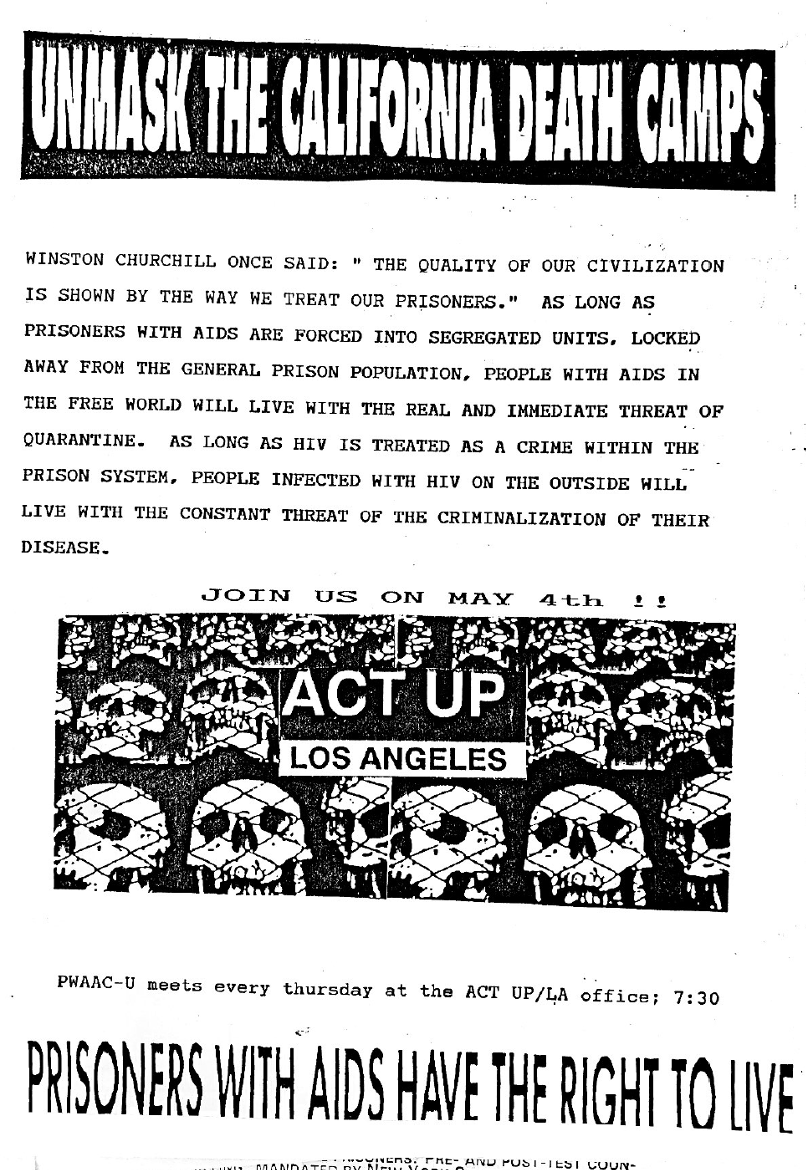

The second major theme I observed through ACT UP/LA’s records was that ACT UP persistently described prison issues as affecting—or at least potentially affecting—everyone living with HIV. As a flier for the protest at the California Department of Corrections put it, “As long as HIV is treated as a crime within the prison system, people living with HIV on the outside will live with a constant threat of the criminalization of their disease.” The members of ACT UP/LA were predominately white, middle-class men who had never been incarcerated. Yet many had experienced police harassment at gay bars or faced police brutality in protests. They held real fears of AIDS quarantine stemming from the 1986 LaRouche initiative (Proposition 64). Many were also highly concerned over HIV criminalization laws, which grew through requirements imposed by the 1990 Ryan White Care Act, a major source of AIDS funding.

The members of ACT UP/LA thus found many reasons to care about the issue of HIV/AIDS in prisons. A few, like Mary Lucey, were directly affected: they were formerly incarcerated and living with HIV, or had loved ones with these experiences. Others cared because they identified as marginalized subjects in AIDS politics, and felt that bringing marginalized issues to the center—addressing gender, race, class—was essential to ending the epidemic. This viewpoint compelled many in the Women’s Caucus as well as many people of color in ACT UP. Still others cared about AIDS in prisons for a seemingly opposite reason: because they lived at the very center of ACT UP’s work, as gay men and as people with HIV. As I move forward with my research, I am compelled by a sense that these impulses, seemingly so different, could in fact reinforce each other—enabling activists to more firmly oppose the binary between “deserving” and “innocent,” and to more fiercely claim the value, and fight for the survival, of all people living with HIV and AIDS.

Image Credits

Top image: ACT UP/LA Women’s Caucus, flier for November 30, 1990 demonstration at Frontera Women’s Prison, Box 7, Folder 14, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles, CA.

Bottom image: Prisoners With AIDS Advocacy Committee United (PWAACU), “Unmask the California Death Camps” flier for May 4, 1992 protest in Sacramento, Box 1, Folder 40, Judy Sisneros Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles, CA.

Emily K. Hobson is a historian of radical movements, LGBTQ politics, and HIV/AIDS in the United States. She is the author of Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (University of California Press, 2016) and co-editor of Remaking Radicalism: A Grassroots Documentary Reader of the United States, 1973-2001 (University of Georgia Press, forthcoming 2020). Hobson serves as Associate Professor of History and Gender, Race, and Identity, and as Associate Director of Gender, Race, and Identity, at the University of Nevada, Reno. Additionally, she serves as Co-Chair of the Committee on LGBT History. She earned her PhD in American Studies and Ethnicity from the University of Southern California. Her current research addresses activism against HIV/AIDS in prisons in the 1980s and 1990s United States.